Cropping Photos: Creativity, Discipline, and Exercises

Some photographers, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, famously refused to crop their photographs. Cartier-Bresson argued that cropping a photo rarely improves a photo because of the limitations of human vision. But in today’s world, where digital photography workflows are the norm and cropping a photo is as easy and precise as can be, does this idea still hold true? In this article, I explore arguments for and against cropping photographs and suggest some exercises that could help improve your relationship to this important photography technique.

Arguments for and against

So why may cropping your photographs be a bad thing? Some commenters from the comment brigade across the internet have argued that cropping your photos is lazy, as Eric Kim argues. Relying on cropping your photographs to get a good image means you don’t pay enough attention to image composition in the moment.

At least one comment I read claimed that photography course professors strongly discourage cropping, possibly because the instructors want students to focus more on image composition earlier in the creative process. Challenging yourself as the photographer to go out and take photos that work without cropping really forces you to stay in the moment during a photo shoot. This sort of arbitrary limit or challenge can also summon the spirit of creativity. If nothing else, improving your composition in-camera can save you time on post-production back at home.

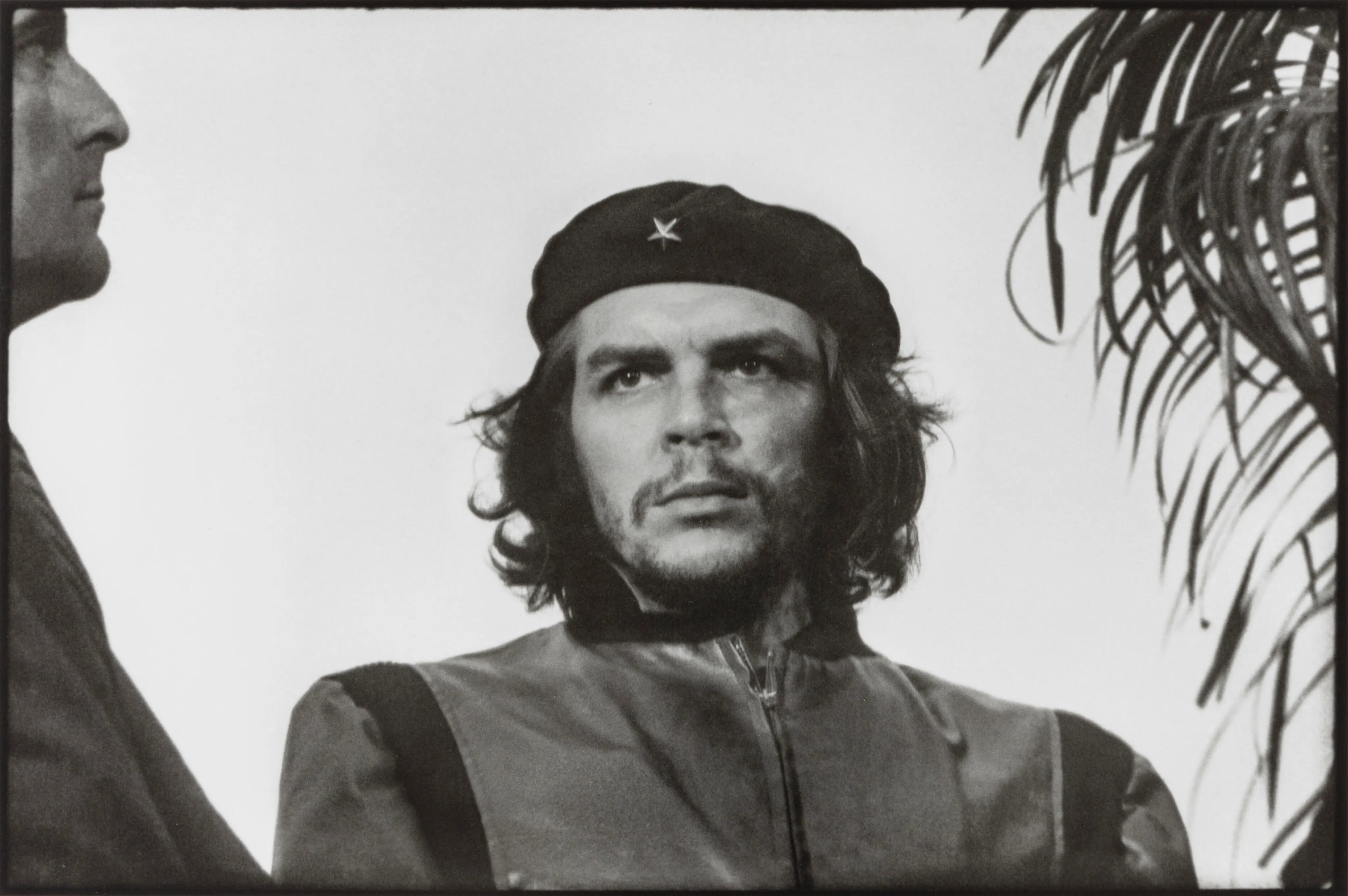

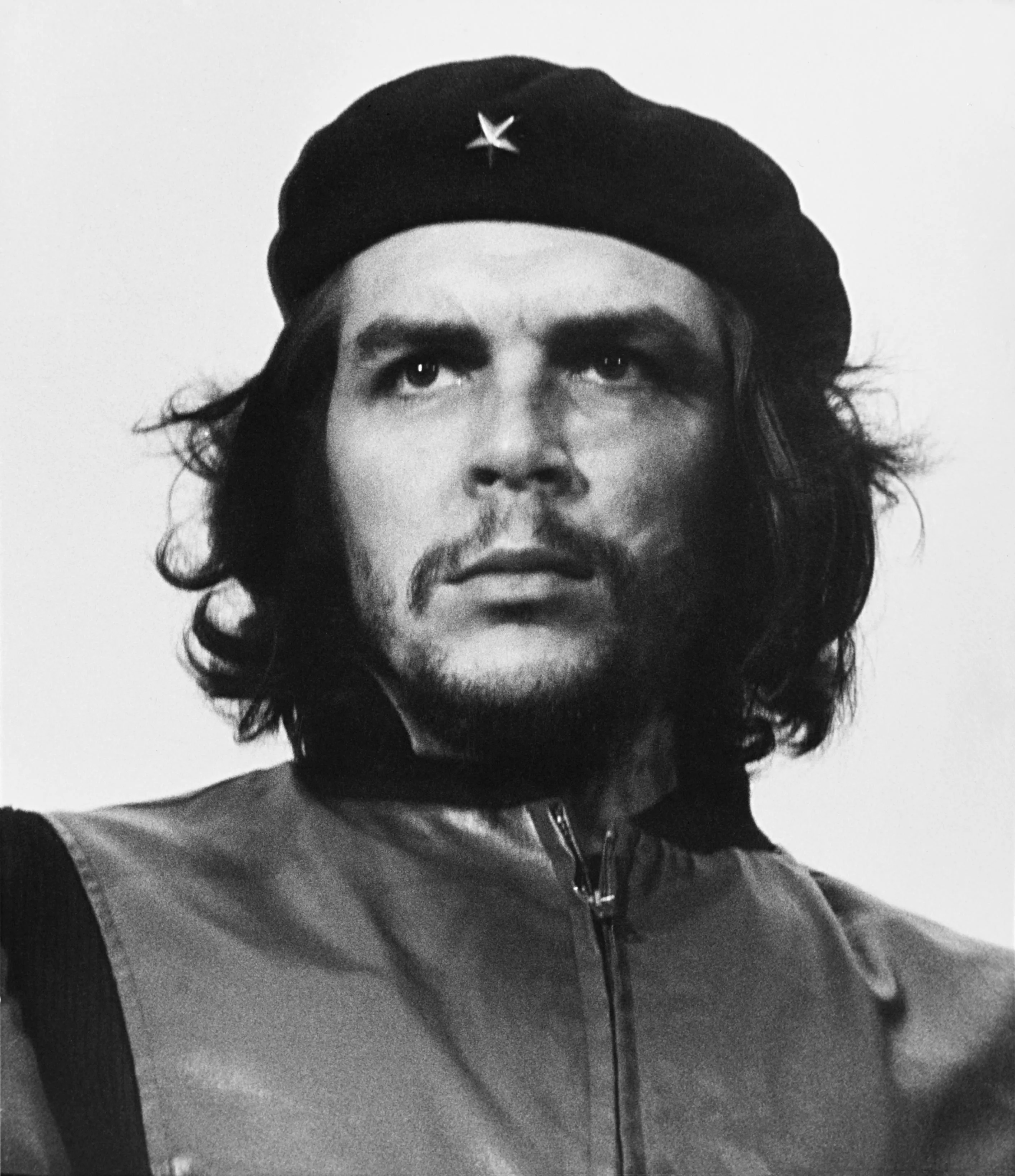

On the other hand, cropping is a creative and corrective tool that photographers have been using since long before the digital era. Many of the most famous photographs ever taken were cropped from their original forms. A commonly cited example is the iconic picture of Che Guevara. The final version probably needs no introduction, but you can compare them below:

The impact of Alberto Korda’s famous photo was greatly increased by the use of cropping.

A comparison to music recording

Cropping is much like any tool or technique available to the creator—experience teaches us when and how to use it. I liken cropping to a common technique used in music recording: punching in/out. A typical song on the radio is rarely a single complete, uninterrupted performance. Rather, during the recording process, the mixing engineer may splice together many recorded takes to select the best parts of each take. If done well, the final result sounds like a single take, but without any “imperfections.” Mixing engineers do this because of time constraints and the impracticality of getting a single, perfect take from a performer. If you’ve ever tried to record music, you know just how frustratingly elusive a perfect take is.

Below is a quick video showing how the process works in a typical digital audio workstation. You can start at 1:20 in the video to see an example of how the technique is used to correct a previous performance.

Much like cropping, punching in/out has been around for a long time. And much like cropping, it has gotten easier to do with the advancement of technology. Like in the video above, all it takes to punch in now is a single press of a key on a keyboard.

Before digital technology, the process was difficult and risky. But now, it’s so straightforward that it has even become an integral part of the creative process for many musicians. The New York Times, for example, published a video detailing how rappers no longer write down their lyrics before entering the studio to record. Instead, they just punch in/out to record their ideas one line at a time until the song is finished.

In the video, music producer Just Blaze reflected on the change in creative techniques, saying “You can’t really hold your technique over a younger generation’s head, right? It is about just getting the best end result.”

I don’t necessarily agree that the end result is all that matters. By that view, AI-generated music is good if it sounds good, even if it is just a mashup of previously observed data, compiled into vectors of statistical relationships. The same could be said of most of what humankind does. In the not-too-distant future, we may come to see a time in which AI can do almost everything better than humans can, and we may need to ask ourselves, why do anything at all? Why bother? I digress.

But returning to the issue of cropping, the technique is easier to use than ever. This makes it more important than ever to understand the why behind the technique. Why might you want to crop a photo? It might be to remove something on the edge of a frame that negatively affects the composition. The goal could also be more creative, like entirely changing the subject, as Elliott Erwitt did in the famous photo of the chihuahua at a woman’s feet on the street (see that Eric Kim article to see what I mean).

To sum up, cropping has been an integral part of the photographer’s toolkit since long before digital photography made it so easy to do. So, what does this all mean for the modern photographer? In an era of limitless possibilities, we need to have the discipline to impose our own artificial limitations to avoid getting lost creatively. To that end, here are some suggestions for exercises to practice effective cropping.

Cropping exercises

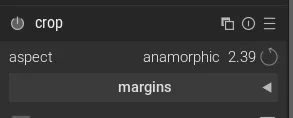

There are several aspects to play around with during cropping. One is to experiment with different aspect ratios. Most cropping tools make it easy to impose a particular aspect ratio on the crop, just as shown in the screen capture of Darktable’s cropping module below:

Darktable’s crop module has many predefined aspect ratios for you to choose from.

Try cropping to an aspect ratio you don’t normally use. For me, since the slots in my family photo album are 3.5" × 5", this is the format I most often crop to. A challenge for me would be to only crop my photos to some other ratio, like 1:1 or a more cinematic 2:1.

Another challenge would be to crop horizontal images into portrait orientation. I’ve found it quite difficult to make good photos this way, but it’s a great exercise, nonetheless, to really focus in on the photo’s subject.

Lastly, perhaps the greatest challenge of all is to decide before a particular photo shoot that you aren’t going to crop any of the photos at all. This forces you to really consider the framing and composition of every shot. It forces you to focus on the technique of capturing the photo, paying attention to details you might not have noticed before. Focusing on your technique is a great way to improve, even if you don’t make the ascetic commitment never to crop your photos again.

See the end of the article for some of my own experiments with different aspect ratios.

Parting thoughts

Technology has made cropping an image an incredibly simple process. As photographers, we should consider our relationship to this tool and others that are available to us. By consciously choosing to use them (or not), we improve our skills and knowledge of the craft. It helps us understand our own preferences by moving us out of our comfort zones into a new way of doing things. I hope this was helpful to you.

Gallery

Here are some examples of my own experiments in cropping. Click on images to open the galleries for a closer look.

A variety of anamorphic (2.39:1) and square crops (all images originally 3:2). These images were taken at the Cottage Café in Wukang Mansion, Shanghai.

Rocks in a pond at Ryōan-ji, Kyoto. Square cropping forces a re-evaluation of the subject.

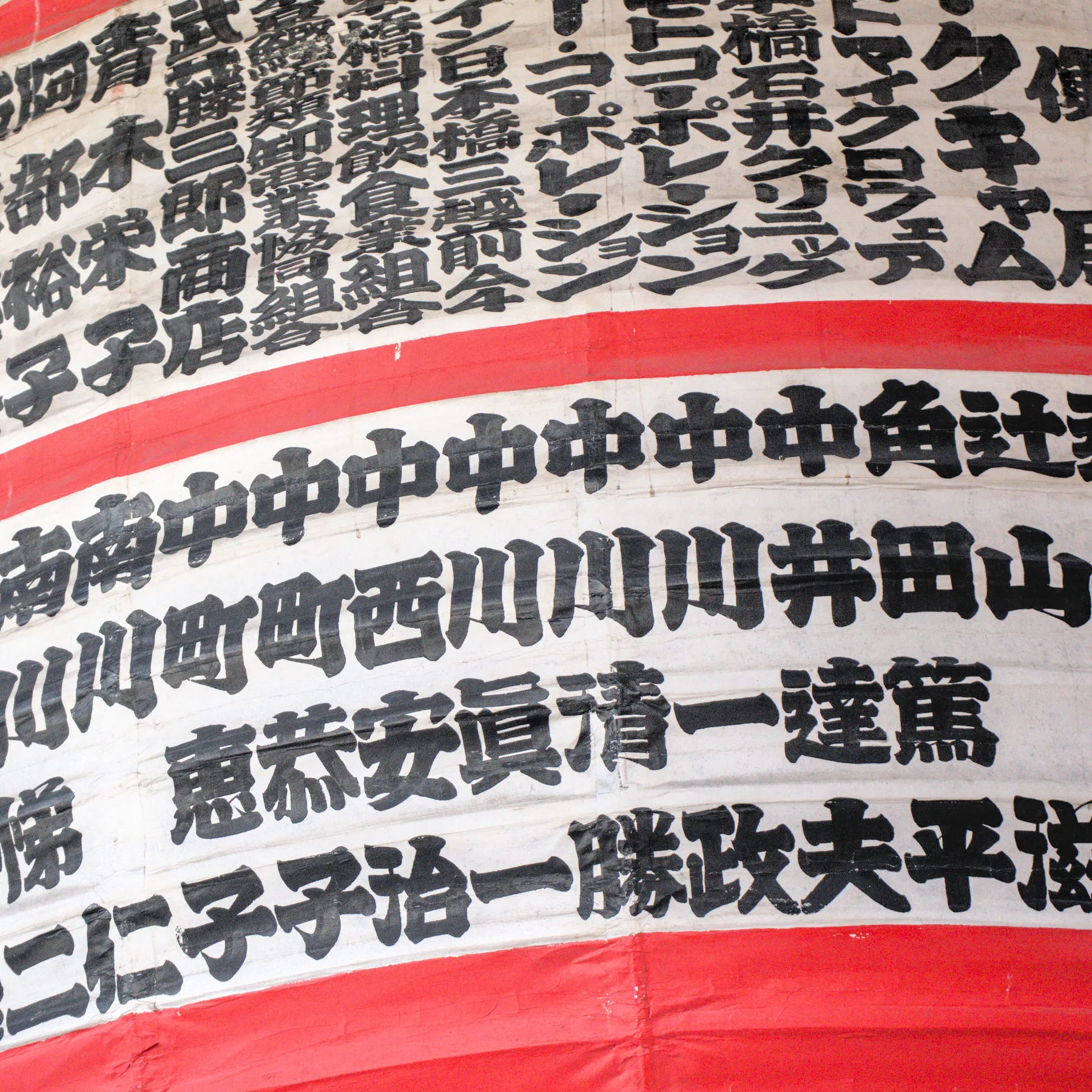

A bronze statue and a red lantern at Sensō-ji, Tokyo. Square aspect ratio is difficult to make look good, in my opinion. But with a 2:1 ratio, you can put together two images to make a square, which makes for an interesting effect.

My parents’ cat. The cinematic crop really changes the mood of the image.