How Information Theory Can Improve Your Photo Organization

Ever tried in vain to find one photo out of the thousands you’ve taken? One person I know has more than a decade’s worth of photos on her phone, and I don’t know how she finds anything. One solution to the organization problem is to just accept the chaos. If you do try to tackle it, remember that there is no perfect system—but many systems can be adequate. If you’re like me, it helps to have a principle to support your organizing efforts.

To that end, I’ll take you on a nerdy walk through two different information organization principles and discuss their faults and merits as they apply to image organization. Then, I’ll show you how I apply them to my own photo collection.

Separating images by function

The most important reason to bother organizing images at all is to be able to find your photos after you’ve taken them. However, different organizational structures imply different cognitive models, affecting the mental processing needed to find what you’re looking for. Let’s compare two possible structures for storing photos. This first one below is similar to what Darktable uses by default:

Darktable images/

└── 20240601_Some event/

├── 20240601_001.arw

├── 20240601_002.arw

├── 20240601_003.arw

└── Exports/

├── 20240601_001.jpg

├── 20240601_002.jpg

└── 20240601_003.jpg

3 directories, 6 files

Raw image files are stored in their usual folders under some main directory. After those images are processed, they are exported into an Exports folder inside the same directory as the source raw files. Semantically, this folder structure implies a relationship between the raw images and the exports. To find those exported images, you first have to remember the “narrative” of them as being part of that “Some event” photo shoot. This is a process-oriented cognitive model: take the pictures, then develop them, then export them.

That’s a really common way to organize photos, but I think it could be improved. Compare that with the following system:

001_Raw images/

└── 20240601_Some event

├── 20240601_001.arw

├── 20240601_002.arw

└── 20240601_003.arw

002_Exports/

└── 20240601_Some event

├── 20240601_001.jpg

├── 20240601_002.jpg

└── 20240601_003.jpg

4 directories, 6 files

In this system, the exported images no longer have an explicit relationship to the source raw files. Instead, images are organized by their function in what’s called a “faceted classification system” (see Wikipedia). Facets are properties or characteristics of a subject. In this case, the function of the image is the top-level facet. Here, they are grouped into two functions, “raw” input and processed “export.”

Benefits of organizing by function or purpose

This functional cognitive model has several benefits for finding your photos fast. First, the shallower hierarchy means fewer clicks to find an image. No one needs repetitive stress injuries from clicking so many folders!

Second, the functional model is easier on working memory. You start with “I’m looking for an exported image,” and go from there. The shallower, step-by-step navigation means you have to hold less information in mind during your search. In contrast, the process-oriented model requires you to remember the context of the image before you can begin to search for it. It also makes it more difficult to browse exports from multiple shoots because they aren’t siblings in a single folder.

Another benefit of the functional scheme is that it allows more flexibility in grouping exports. For example, you can use the export date and a custom name, grouping images by export session instead of shooting session. This can be helpful, for example, when selecting images from several shooting sessions to be used in a blog post. When they are exported, they can all be exported into the same folder to make them easy to find.

I also like that the folders feel clean when browsing. I use Darktable to manage and process camera raw image files, but I prefer to use my file manager to manage other formats like JPEGs. When exports are in their own directory, I don’t have to wade through hundreds or thousands of .ARW images and their XMP sidecar files. It looks cleaner, and it’s quicker to navigate.

File naming is another consideration. Make sure both the folders and files have the full date in YYYYMMDD format, and use a descriptive filmroll name (a filmroll is Darktable’s fancy word for folder). I discuss the import process and introduce some of Darktable’s terminology in another article.

To sum up, keeping all exports under a separate folder makes a shallower folder structure that requires fewer cognitive resources to navigate, speeding up the search process. Giving folders descriptive names and using the full date in YYYYMMDD format also makes searching for images fast.

My personal setup

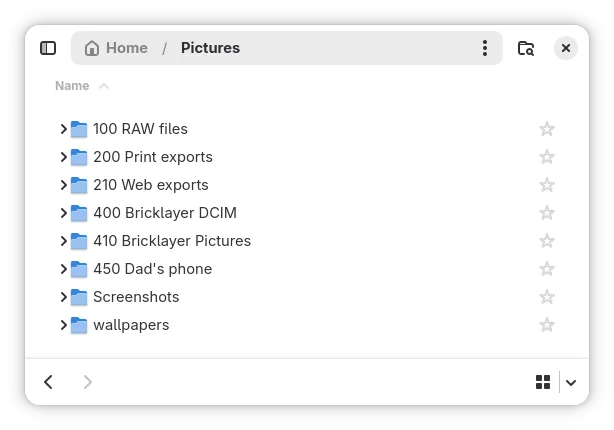

Using a functional structure keeps photos easy to manage.

These directories live in my Pictures folder on my computer. The numbers suggest a workflow order. 100 Raw files is where I store all of Darktable’s filmrolls. Next are the 200-level folders, which contain exports for various purposes.

I separate my exports into two different directories: one for exports to be printed, and one for exports to be used on the web (e.g. Instagram or my blog). I find this separation works well for me—I set up Darktable export presets for each of these folders, with custom settings for picture size and file format.

Below the 200-level folders are the 400-level folders, which are image folders synchronized from other devices. (I gave my cell phone a random name, “Bricklayer”—I’m not good with names.) My Android phone has both a DCIM and a Pictures folder, and I synchronize them to my computer using Syncthing.

No system is perfect. Once you have enough photos, managing them becomes challenging no matter what you do. But separating the exports from the rest helps me focus on the workflow. I can browse images without too much jumping between folders, and the dates in the file and folder names make finding them quick.

At the end of the day, a good organization system helps. You don’t have to give in to the chaos like my friend did. Find a system that fits how you think—a system that’s good enough. Don’t let it get in the way of actually taking photos. Accept the limits of your time and order, pick up your camera, and get out there.